In the world of corporate finance, traditional budgeting processes often rely on rigid frameworks and top-down approaches. However, a new wave of thinking, rooted in behavioral economics, is transforming how companies manage their finances. Let's delve into the story of Vikram, a forward-thinking CFO, who has been experimenting with subtle psychological cues to enhance his company's financial planning.

Vikram's journey began with a simple yet powerful concept: the way information is presented can significantly influence decisions. This is known as "framing" in behavioral economics. Instead of presenting budget cuts as harsh reductions, Vikram framed them as "efficiency gains." This positive spin helped employees see the cuts not as losses, but as opportunities to streamline operations and improve overall efficiency.

One of the most effective tools in Vikram's arsenal was the use of default options. In traditional budgeting, employees might be given a range of choices on how to allocate funds, but these choices often require active decision-making. By setting default options that encourage savings, Vikram leveraged the power of inertia. For instance, when setting up employee retirement plans, the default option was to contribute a significant portion of their salary, rather than opting out. This simple change led to a significant increase in retirement savings across the company.

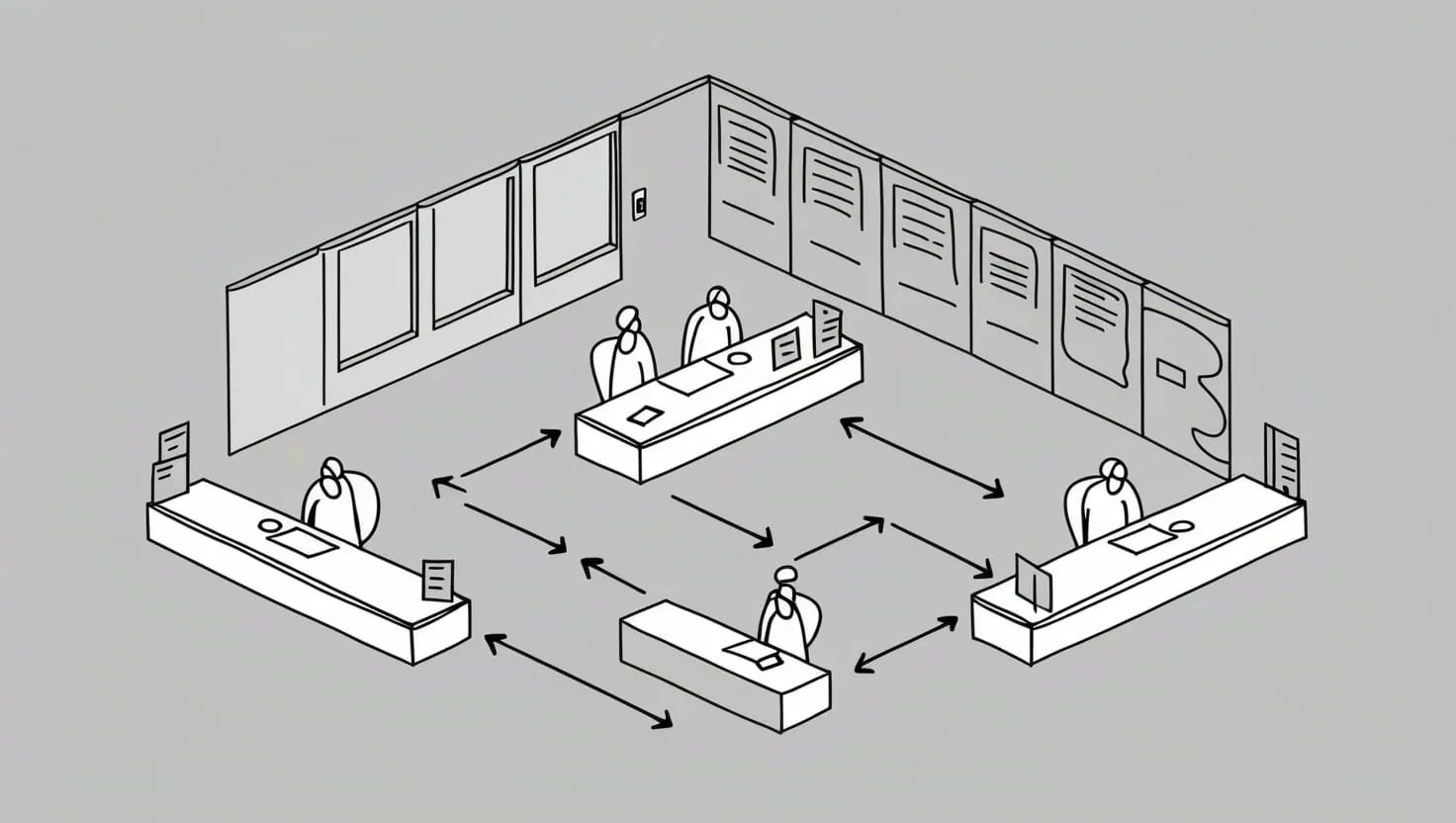

Choice Architecture

The concept of choice architecture plays a crucial role in Vikram's approach. This involves designing the environment in which choices are made to influence the decisions that are ultimately taken. In corporate budgeting, this can mean structuring budget categories in a way that encourages responsible spending. For example, Vikram created separate mental accounts for different budget items, such as "operational costs" and "research and development." By doing so, he made it clearer to department heads that money allocated to one category could not be easily transferred to another, much like how individuals treat different accounts in their personal finances.

Loss Aversion

Loss aversion is another key principle that Vikram utilized. People generally fear losses more than they value gains. To capitalize on this, Vikram presented budget decisions in terms of what could be lost rather than what could be gained. For instance, when discussing potential budget cuts, he highlighted the potential losses if the company did not reduce costs, rather than the savings that could be achieved. This approach made the decision to cut costs more palatable and urgent.

Social Proof

Social proof, or the influence of social norms, is a powerful motivator in any organization. Vikram used this to his advantage by sharing stories of other departments or companies that had successfully implemented similar budgeting strategies. By showcasing these success stories, he created a sense of community and shared purpose, encouraging more departments to adopt the new budgeting practices.

Mental Accounting

Mental accounting, a concept where people treat different types of money differently, was also a key strategy. Vikram designated specific accounts for different types of expenses, making it clear that money in one account was not fungible with money in another. This helped in avoiding the sunk-cost fallacy, where decisions are influenced by past investments rather than future benefits. For example, if a project was not yielding the expected returns, the money allocated to it was not seen as a sunk cost that needed to be recouped, but rather as an investment that could be cut if it was no longer viable.

Nudges in Tax Compliance

While Vikram's focus was on corporate budgeting, the principles he applied are also relevant in broader financial contexts, such as tax compliance. In many countries, tax evasion is a significant issue, often due to complex tax codes and cognitive overload. By simplifying the tax compliance process and using behavioral nudges, governments can increase tax collection rates. For instance, in Argentina, embedding behaviorally-informed messages directly into tax bills, such as highlighting the penalties for non-compliance or the public works funded by taxes, led to a significant increase in tax compliance.

Boosts and Sludge

In addition to nudges, Vikram also considered the concepts of "boosts" and "sludge." Boosts refer to interventions that enhance the cognitive abilities or motivation of individuals, making them better equipped to make informed decisions. Sludge, on the other hand, refers to the friction or obstacles that make it harder for people to make good choices. In corporate budgeting, reducing sludge could mean simplifying budgeting processes, providing clear and timely information, and ensuring that decision-makers have the necessary tools and training. By boosting the capabilities of his team and reducing sludge, Vikram created an environment where financial decisions were more informed and effective.

Personal Touches and Engagement

To make the budgeting process more engaging, Vikram introduced personal touches that resonated with his team. He recognized that financial planning is not just about numbers, but also about the people involved. By involving department heads in the budgeting process and giving them a sense of ownership, he increased their commitment to the financial goals. For example, he organized workshops where teams could discuss their budget allocations and set their own targets, making the process more collaborative and inclusive.

Long-Term Financial Goals

One of the most significant challenges in corporate budgeting is aligning short-term decisions with long-term financial goals. Vikram addressed this by using commitment strategies and guilt as tools to ensure that the "doer" (the person making the day-to-day decisions) aligned with the "planner" (the person setting the long-term goals). For instance, he set up a system where department heads had to justify any deviations from the budget plan, which helped in maintaining a focus on long-term objectives.

Real-World Examples

The success of Vikram's approach can be seen in various real-world examples. In one instance, a company implemented a default option for energy-efficient lighting in their new office building. This simple nudge led to a significant reduction in energy costs without requiring any active decision-making from employees. Another example is from a municipality in Argentina, where rewarding citizens for paying their taxes on time led to a noticeable increase in tax compliance rates.

Conclusion

Vikram's story highlights the transformative power of behavioral economics in corporate budgeting. By leveraging subtle psychological cues, framing budget decisions positively, using default options, and reducing sludge, companies can make their financial planning more effective and aligned with long-term goals. As we navigate the complexities of modern finance, it is clear that traditional top-down approaches need to be complemented with a deeper understanding of human behavior. By doing so, we can create a more engaging, efficient, and responsible financial management system that benefits everyone involved.