In the intricate web of global economics, tax havens play a role that is both fascinating and contentious. These jurisdictions, often small and strategically located, have become pivotal in the international financial landscape, attracting vast amounts of wealth and influencing the economic fortunes of nations worldwide.

Let’s start with the Cayman Islands, a Caribbean archipelago that has transformed into a powerhouse of offshore financial services. Here, the absence of corporate taxes and stringent financial regulations creates an environment where companies can minimize their tax liabilities. This setup is particularly appealing to multinational corporations seeking to optimize their profits. However, this optimization comes at a cost; it results in significant revenue losses for the countries where these companies operate, exacerbating economic inequalities and slowing down recovery during financial crises.

Switzerland, with its storied history of banking secrecy, offers a different yet equally compelling narrative. The Swiss banking system, built on the principles of confidentiality and anonymity, has long been a magnet for wealth management. The Banking Law of 1934 cemented this reputation, making it a crime for banks to disclose client information without authorization. While recent regulations have introduced stricter Know Your Customer (KYC) rules and automatic information-sharing agreements to combat money laundering and tax evasion, the allure of Swiss banking remains strong. This secrecy, however, raises ethical questions about the facilitation of tax evasion and corruption, particularly during times of economic instability.

Luxembourg, often referred to as the “place to be” for investment funds in Europe, presents another facet of the tax haven phenomenon. The Grand-Duchy is home to a sophisticated framework for setting up and managing investment funds, including the popular SICAV (investment companies with variable capital) and SICAF (investment companies with fixed capital) structures. These funds can be structured as stand-alone entities or as part of an umbrella structure with multiple sub-funds, each with its own set of assets and liabilities. This complexity allows for flexible and efficient asset management but also creates opportunities for tax optimization that can be detrimental to other countries’ tax revenues.

Singapore, with its low-tax regime and robust financial infrastructure, has emerged as a significant financial hub in Asia. The city-state’s business-friendly environment and competitive tax rates make it an attractive destination for both individual wealth and corporate investments. However, this low-tax environment also means that Singapore benefits at the expense of other nations, which lose out on potential tax revenues. The impact is twofold: while Singapore thrives economically, other countries face reduced government revenues, which can hinder their ability to fund public services and infrastructure.

Ireland, known for its corporate-friendly tax policies, has become a haven for tech giants and other multinational corporations. The country’s low corporate tax rate and favorable business environment have made it an ideal location for companies like Google and Apple to establish their European headquarters. While this has brought significant economic benefits to Ireland, it has also raised concerns about tax fairness and the erosion of tax bases in other countries. The international community has increasingly scrutinized Ireland’s tax policies, leading to ongoing debates about the balance between attracting foreign investment and ensuring fair taxation.

The Netherlands, often described as a conduit country for international tax planning, plays a unique role in the global tax landscape. Its extensive network of tax treaties and favorable tax regime make it an intermediary through which multinational corporations can channel their profits, often to other tax havens. This setup allows companies to minimize their global tax liabilities, but it also raises questions about the fairness and transparency of international taxation. The Dutch “Dutch Sandwich” and “Double Irish” structures, for example, have been criticized for facilitating aggressive tax planning that deprives other countries of their rightful tax revenues.

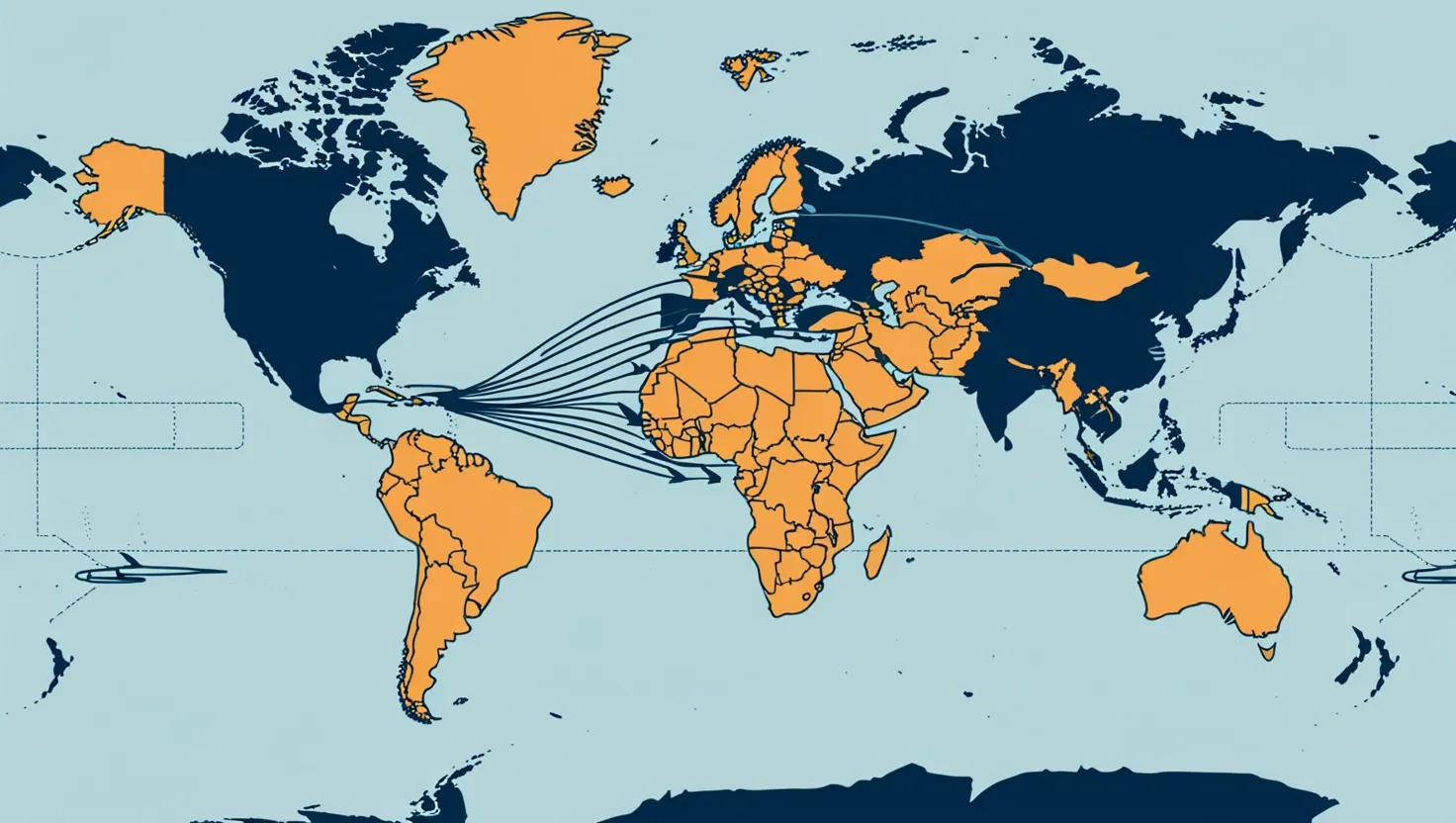

The impact of these tax havens on global wealth distribution is profound. By providing avenues for tax avoidance and evasion, they contribute to a significant loss of tax revenues for many countries. This loss is particularly burdensome during economic crises, when governments need robust tax bases to fund recovery efforts and support vulnerable populations. The consequence is a skewed distribution of wealth, where a small elite benefits at the expense of the broader population.

International efforts to combat tax evasion and promote transparency have been ongoing but challenging. Initiatives such as the Automatic Exchange of Information (AEOI) and the Common Reporting Standard (CRS) aim to reduce tax evasion by mandating the exchange of financial information between countries. However, the effectiveness of these measures depends on the cooperation of all participating nations, and loopholes often remain.

The economic benefits of tax havens are clear for the jurisdictions themselves; they attract significant foreign investment, stimulate economic growth, and create jobs. However, these benefits come at a cost to other nations, which face reduced tax revenues and increased economic inequality. The ethical implications are stark: while tax havens facilitate wealth accumulation for a few, they exacerbate poverty and inequality for many.

As we consider potential reforms in global taxation, it becomes evident that a more equitable and transparent system is necessary. This could involve harmonizing tax rates across countries, implementing stricter regulations on tax avoidance, and enhancing international cooperation to close loopholes. The OECD’s Base Erosion and Profit Shifting (BEPS) project is a step in this direction, aiming to ensure that profits are taxed where economic activities take place and value is created.

In conclusion, the world of tax havens is complex and multifaceted, with both economic and ethical dimensions. While these jurisdictions offer attractive environments for wealth management and corporate optimization, their impact on global wealth distribution and government revenues is significant. As we move forward, it is crucial to strike a balance between attracting investment and ensuring fair and transparent taxation. Only through such reforms can we create a more equitable global economic system where wealth is distributed more justly and governments have the resources they need to support their citizens.