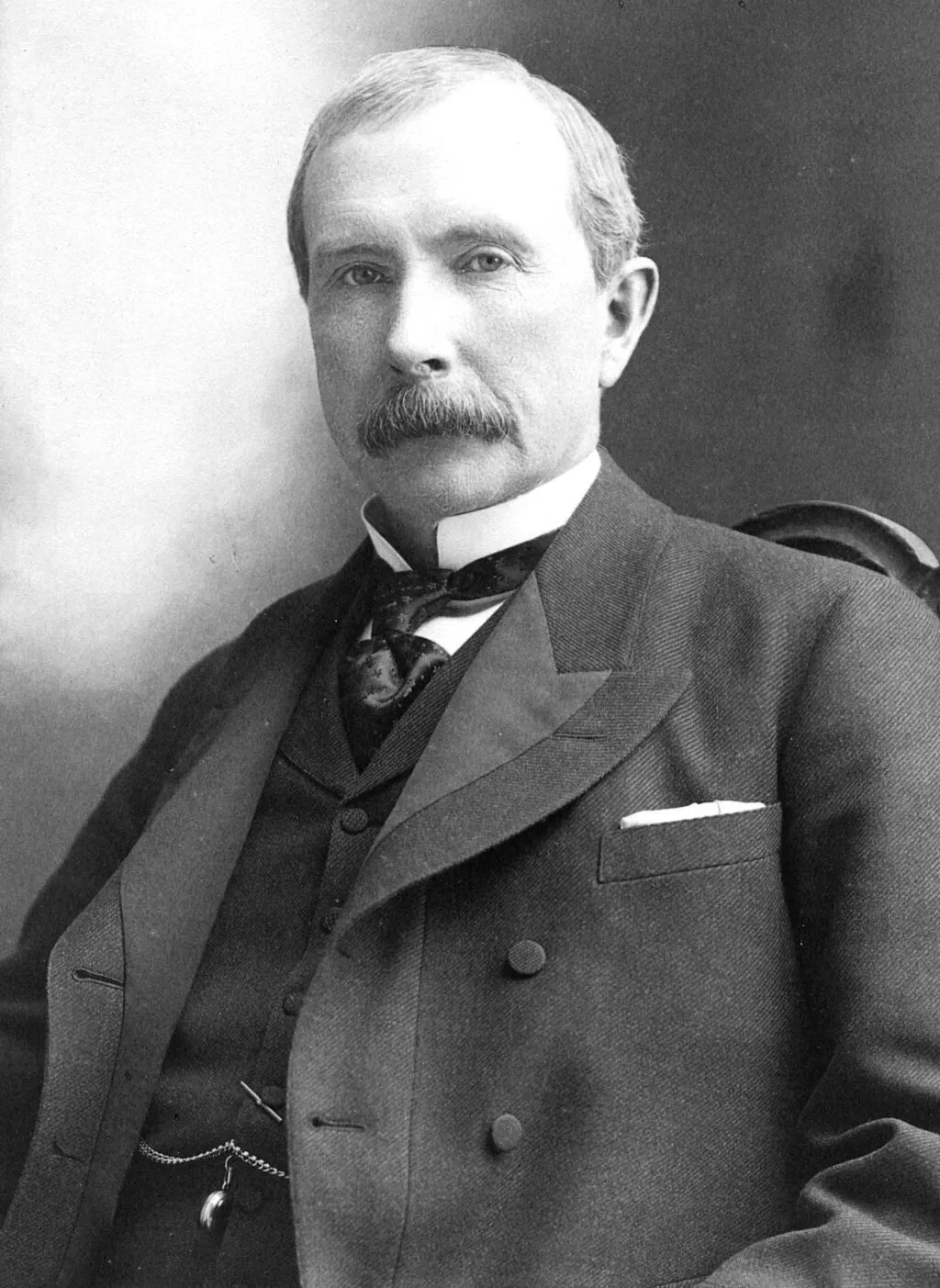

John D. Rockefeller’s name evokes both admiration and controversy. As the world’s first billionaire, he not only amassed an unprecedented fortune but also shaped the landscape of modern industry. His company, Standard Oil, became synonymous with monopolistic power and ruthless business tactics. Rockefeller's rise from poverty to the pinnacle of wealth is a story filled with ambition, rivalry, and relentless drive. While his methods sparked public outrage and government intervention, his later philanthropic efforts left a lasting positive legacy. Understanding Rockefeller's influence involves exploring both his formidable business acumen and the complex ethical questions surrounding his practices.

Humble Beginnings

John D. Rockefeller was born on July 8, 1839, in Richford, New York, into a life of stark poverty. His father, William Avery Rockefeller, known as "Devil Bill," was a charismatic but unscrupulous man who led a double life as a con artist. Devil Bill’s frequent absences left young John and his siblings to fend for themselves. Despite these hardships, Rockefeller's mother, Eliza, instilled in him a strong work ethic and a deep sense of duty. She was the steadying force in his life, teaching him the value of discipline and hard work.

John’s early years were marked by a constant struggle for survival. The family often lived in dilapidated houses, wore tattered clothes, and went to bed hungry. Despite these challenges, young John showed an early knack for making money. He undertook small ventures like raising turkeys and selling their eggs, gradually learning the basics of commerce. These formative experiences laid the groundwork for his future business endeavors, teaching him resilience and ingenuity. The harsh realities of his childhood would shape his relentless pursuit of financial stability and success, setting the stage for his rise in the business world.

First Steps in Business

John D. Rockefeller’s journey into the business world began in earnest when he was just 16 years old. With his father often absent, the responsibility of supporting the family fell heavily on his shoulders. Rockefeller had dreams of attending college, but financial constraints made that impossible. Instead, he decided to enter the workforce and secure a job to help his family.

Determined to make something of himself, Rockefeller meticulously prepared for his job search. He created a list of the largest companies in Cleveland, including railroads, banks, and wholesale merchants. Armed with this list, he set out each day to visit these businesses, seeking employment. Despite his youth and lack of formal education, Rockefeller was undeterred by the countless rejections he faced. Many potential employers laughed at the idea of hiring a 16-year-old, but Rockefeller’s persistence never wavered.

After six weeks of relentless searching, Rockefeller finally secured a position as an assistant bookkeeper at Hewitt & Tuttle, a small produce commission firm. His excellent penmanship and attention to detail impressed his employers, who offered him the job without even discussing his salary. For Rockefeller, this moment was a breakthrough. He celebrated September 26th, the day he was hired, as "Job Day" for the rest of his life, considering it more significant than his own birthday.

Rockefeller’s first job taught him invaluable lessons about business operations, from handling invoices to managing finances. He quickly demonstrated his worth, taking on more responsibilities and proving himself to be a diligent and trustworthy employee. This early experience not only honed his skills but also fueled his ambition. He began to dream of greater things, constantly reminding himself, “I am bound to be rich.” This self-assured mantra would drive him throughout his career, propelling him from a humble bookkeeper to the world’s first billionaire.

Building the Produce Business

Having gained valuable experience at Hewitt & Tuttle, John D. Rockefeller was ready for a bigger challenge. In 1859, he partnered with Maurice B. Clark, a young chemist he had befriended. Together, they formed a produce commission business called Clark & Rockefeller. Their company focused on buying and reselling goods such as grain, fish, meat, and other food products. This venture marked Rockefeller's first significant step into entrepreneurship.

Starting a new business was not easy. Rockefeller and Clark faced numerous challenges, from finding reliable suppliers to building a customer base. They spent long hours on the road, seeking clients and negotiating deals. The work was exhausting, but Rockefeller's determination and meticulous nature soon paid off. He was particularly skilled in keeping detailed records, which helped them manage their finances effectively.

One of the key factors that set Clark & Rockefeller apart was Rockefeller’s ability to build trust with their clients. Despite being relatively young, he exuded a maturity and seriousness that impressed older businessmen. His clients often referred to him as "Mr. Rockefeller," a sign of the respect he commanded. This trust helped their business grow steadily, even in the face of stiff competition.

However, they quickly realized that their business needed more capital to expand. Rockefeller and Clark devised a clever strategy to secure loans from banks. They would publicly announce that their firm was looking to invest $10,000, even if they only needed $5,000. This gave the impression that they had substantial funds, making banks more willing to lend to them. This tactic worked, and they were able to secure the loans necessary to scale their operations.

The outbreak of the American Civil War in 1861 brought an unexpected boom to their business. The Union Army’s demand for food supplies skyrocketed, driving up prices and profits. By 1862, Clark & Rockefeller had cleared a profit of $177,000, a significant sum for the time. Rockefeller, a devout Baptist, opposed slavery and supported the Union’s cause, but he was also acutely aware of his responsibility to his family. He paid for a substitute to serve in the army on his behalf, ensuring that he could continue to provide for his relatives.

The success of Clark & Rockefeller laid the foundation for Rockefeller’s future endeavors. It proved his ability to thrive in the competitive world of business and reinforced his belief in the power of careful planning and strategic thinking. This venture also taught him the importance of diversifying his investments, a lesson that would be crucial in his later ventures in the oil industry.

The Move to Oil

The booming success of the produce business wasn’t enough to satisfy John D. Rockefeller's ambitions. In the early 1860s, he saw a new opportunity that would change his life and the world: the oil industry. The discovery of crude oil in Titusville, Pennsylvania, in 1859 sparked a rush similar to the California Gold Rush. This "black gold" was in high demand for lighting and lubrication, and Rockefeller recognized its vast potential.

In 1863, Rockefeller and Maurice Clark decided to invest in a new oil refinery in Cleveland, Ohio. They partnered with Samuel Andrews, a skilled chemist who had developed an efficient process for refining crude oil into kerosene. Kerosene was a superior product for lighting, providing brighter and longer-lasting light than crude oil. Andrews’ refining process, which used sulfuric acid to purify the oil, was a game-changer.

Rockefeller and Clark initially viewed the oil business as a side venture, continuing to run their produce business while Andrews managed the refinery. However, it quickly became apparent that oil refining was far more profitable. Within a year, their refinery was generating more revenue than the produce business. This success prompted Rockefeller and Clark to go all in on oil, abandoning their produce business to focus exclusively on refining.

The early days of their oil venture were fraught with challenges. The oil industry was highly volatile, with prices fluctuating wildly due to inconsistent supply. Oil could sell for as low as 10 cents a barrel during periods of overproduction and skyrocket to $13 or more during shortages. To mitigate these risks, Rockefeller decided to stay out of the unpredictable oil extraction business and focus solely on refining, where he could maintain more control.

Rockefeller’s meticulous nature and strategic thinking quickly set him apart in the crowded oil market. He understood the importance of efficiency and economies of scale. By improving refining techniques and cutting costs wherever possible, he increased his margins and positioned his refinery as one of the most competitive in Cleveland.

In 1865, a pivotal moment occurred in Rockefeller's career. Maurice Clark wanted to exit the oil business due to the stress of its volatility. Rockefeller saw this as an opportunity to take full control. In a tense auction, he bought out Clark’s share for $72,500, a massive sum at the time, effectively taking on significant debt. This bold move, equivalent to over $1 million today, marked Rockefeller’s first major risk.

With full control of the refinery, Rockefeller rebranded the company as Rockefeller & Andrews. His leadership style was characterized by his intense focus on efficiency and relentless drive to dominate the market. He implemented innovative practices, such as negotiating favorable rates with railroads for transporting oil, which significantly reduced costs and gave his company a competitive edge.

Rockefeller’s ability to foresee the potential of the oil industry and his willingness to take calculated risks set the stage for the creation of Standard Oil. His move into oil was not just about refining petroleum but about transforming an entire industry through innovation, efficiency, and strategic acumen. This period of transition laid the groundwork for Rockefeller’s eventual rise to become the most powerful figure in the oil industry and the world’s first billionaire.

Standard Oil's Rise to Power

With Rockefeller now fully in control of his oil refinery, he embarked on a mission to build an empire. In 1870, he founded the Standard Oil Company, with the goal of creating a vertically integrated monopoly that would dominate the oil industry from production to distribution. This was the beginning of a remarkable journey that would see Standard Oil become one of the most powerful corporations in history.

One of Rockefeller’s first moves was to expand Standard Oil’s refining capacity. He built additional refineries and invested in advanced technology to improve efficiency and reduce costs. His relentless focus on cutting expenses and increasing productivity allowed Standard Oil to produce kerosene at a lower cost than any of his competitors. This competitive advantage was crucial in a market where price was a significant factor.

Rockefeller's strategic genius shone through in his approach to dealing with competitors. Instead of merely competing with them, he sought to control the entire supply chain. He implemented a practice known as horizontal integration, buying out other refineries to eliminate competition and consolidate the market under Standard Oil’s control. By 1872, this aggressive strategy led to what became known as the "Cleveland Massacre," where Rockefeller acquired 22 of the 26 rival refineries in Cleveland.

Rockefeller didn’t just stop at refining. He understood that to truly dominate the oil industry, he needed to control the transportation of oil as well. He negotiated secret deals with railroads to secure favorable shipping rates, known as railroad rebates. These rebates allowed Standard Oil to transport its product at a significantly lower cost than its competitors, who were unaware of the special arrangements. This practice gave Standard Oil a substantial edge, enabling it to undercut prices and drive rivals out of business.

The rebate agreements were not just about lower costs. They also included provisions that provided Standard Oil with detailed information about competitors' shipments, allowing Rockefeller to anticipate and counter their moves effectively. This intelligence gathering was a crucial part of his strategy to dominate the market.

Rockefeller’s ruthless business tactics extended beyond just economic measures. He was known for his ability to use psychological pressure to force competitors into submission. For example, he would slash prices to a point where rivals could no longer sustain their operations, effectively driving them into bankruptcy. Once they were on the brink of collapse, Rockefeller would offer to buy them out at a fraction of their worth, further consolidating his control over the industry.

Despite the ethical dubiousness of these practices, Rockefeller justified them by believing that his consolidation efforts were ultimately beneficial for the industry. He argued that by eliminating wasteful competition, Standard Oil could stabilize prices and ensure a consistent supply of oil, which was essential for the economy.

By the late 1870s, Standard Oil had established itself as a dominant force in the American oil industry. It controlled nearly 90% of the oil refining capacity in the United States, making it one of the first true monopolies in American history. This unprecedented level of control allowed Rockefeller to influence the entire industry, from production to consumer prices.

Rockefeller’s success with Standard Oil was a testament to his extraordinary business acumen and strategic vision. He transformed the oil industry through his innovative practices and relentless pursuit of efficiency. However, his methods also sparked significant controversy and backlash, as many saw his tactics as unfair and predatory. This dichotomy of admiration and criticism would follow Rockefeller throughout his career, shaping his legacy as one of the most influential and polarizing figures in business history.

With Standard Oil firmly established as a powerhouse, Rockefeller was now poised to extend his influence even further, setting the stage for his next ambitious moves in the world of business and beyond.

Nationwide Expansion and Conflict

With Standard Oil firmly established as the dominant force in the oil industry, John D. Rockefeller set his sights on expanding his empire nationwide. This period marked the height of his aggressive expansion and the beginning of numerous conflicts that would define his legacy.

Rockefeller’s first major move outside Cleveland was to establish Standard Oil’s presence in key refining centers across the United States. He targeted cities like Pittsburgh, Philadelphia, and New York, which were vital hubs for the oil industry. By acquiring refineries and integrating them into Standard Oil, he could ensure a steady supply of refined oil to meet the growing demand.

To facilitate this expansion, Rockefeller focused on building a comprehensive transportation network. He understood that controlling the transportation of oil was crucial to maintaining his competitive edge. Standard Oil invested heavily in infrastructure, including pipelines, storage facilities, and tank cars. These investments allowed Standard Oil to transport crude and refined oil efficiently and cost-effectively, reducing its reliance on railroads and further consolidating its control over the supply chain.

However, this expansion did not come without conflict. One of Rockefeller’s most significant battles was with the Pennsylvania Railroad, one of the largest and most powerful railroads in the United States. The Pennsylvania Railroad, under the leadership of Thomas A. Scott, decided to enter the oil business by building its own refineries and pipelines. This move directly challenged Rockefeller’s dominance and sparked a fierce rivalry.

Rockefeller viewed the Pennsylvania Railroad’s entry into the oil business as a direct threat. In response, he launched an all-out attack on the railroad. First, he canceled all shipping contracts with the Pennsylvania Railroad, redirecting Standard Oil’s shipments to other railroads. This action alone caused a significant financial blow to the Pennsylvania Railroad, as Standard Oil was one of its largest customers.

Next, Rockefeller engaged in a price war. He lowered the price of Standard Oil’s kerosene, forcing competitors to match these low prices. Since Standard Oil had lower production and transportation costs due to its scale and efficiency, it could sustain these low prices longer than its rivals, squeezing their profit margins and driving many out of business. This strategy, combined with his ability to secure cheaper transportation rates from other railroads, further weakened the Pennsylvania Railroad’s position.

Rockefeller’s tactics were brutal but effective. The Pennsylvania Railroad struggled to compete, leading to significant layoffs and wage cuts. The economic strain on the railroad industry contributed to widespread labor unrest, culminating in the Great Railroad Strike of 1877. This strike was one of the most violent labor uprisings in American history, resulting in the destruction of railroad property and violent clashes between workers and law enforcement.

Despite the chaos, Rockefeller emerged victorious. The Pennsylvania Railroad, once a formidable opponent, was forced to concede defeat. Rockefeller’s relentless pursuit of control had not only expanded Standard Oil’s reach but also demonstrated his willingness to engage in cutthroat tactics to eliminate competition.

While the Pennsylvania Railroad was a major rival, Rockefeller also faced opposition from other industry figures. His rivalry with Andrew Carnegie, the steel magnate, was particularly notable. Both men were titans of their respective industries and fiercely competitive. Carnegie, who had a personal vendetta against Rockefeller due to their earlier business conflicts, vowed to outdo Rockefeller in terms of wealth and influence. This rivalry pushed both men to greater heights of innovation and expansion, further shaping the landscape of American industry.

As Standard Oil’s influence grew, so did public scrutiny and criticism. Many viewed Rockefeller’s business practices as monopolistic and unethical. His secret deals with railroads, aggressive acquisitions, and price wars drew the ire of the public and the government. Critics argued that Standard Oil’s dominance stifled competition and harmed consumers.

In response to mounting public pressure, the federal government began to take a closer look at Standard Oil’s operations. The era of laissez-faire capitalism was beginning to wane, and calls for regulation and antitrust laws were growing louder. Rockefeller’s empire, built on a foundation of aggressive expansion and conflict, was now facing unprecedented challenges from both the public and the government.

Despite these challenges, Rockefeller remained undeterred. His ability to navigate conflicts, outmaneuver rivals, and adapt to changing circumstances was unmatched. As Standard Oil continued to expand and consolidate its power, Rockefeller prepared for the next phase of his career, which would involve even more dramatic clashes and ultimately reshape the American business landscape.

Scandals and Public Backlash

As John D. Rockefeller’s Standard Oil grew into a colossal empire, it inevitably attracted scrutiny, criticism, and fierce opposition. The company's dominance, built on aggressive tactics and strategic brilliance, soon became a target for public outrage and government intervention.

One of the first significant blows to Rockefeller’s empire came from within the oil industry itself. Independent oil producers and smaller refiners were increasingly vocal about the unfair practices employed by Standard Oil. They accused Rockefeller of using railroad rebates to gain an unfair advantage, engaging in predatory pricing to drive competitors out of business, and forming secret alliances that stifled competition. These accusations painted Standard Oil as a ruthless monopoly that crushed any semblance of fair competition.

The most damaging of these criticisms came from a determined journalist named Ida Tarbell. Tarbell’s father was one of the many small oil producers who had been driven out of business by Standard Oil’s aggressive tactics. Fueled by a personal vendetta and a commitment to exposing the truth, Tarbell embarked on a meticulous investigation into Rockefeller’s empire. Her research culminated in a series of articles published in McClure’s Magazine starting in 1902, which were later compiled into the book "The History of the Standard Oil Company."

Tarbell’s exposé was a detailed and damning account of Standard Oil’s business practices. She uncovered the secret railroad rebates, the coercive tactics used to force competitors to sell out, and the backroom deals that secured Standard Oil’s dominance. Tarbell’s work resonated with the American public, who were increasingly disillusioned with the unchecked power of large corporations. Her portrayal of Rockefeller as a cold, calculating tycoon who manipulated markets and exploited workers struck a chord with readers, further tarnishing his public image.

The growing public outrage, fueled by Tarbell’s exposé, caught the attention of politicians. President Theodore Roosevelt, who had built his political career on fighting corruption and promoting progressive reforms, saw an opportunity to capitalize on the anti-monopoly sentiment. Roosevelt, known for his trust-busting efforts, made it a priority to target Standard Oil. He argued that monopolies like Standard Oil were detrimental to the free market and harmful to consumers.

In 1906, the federal government launched an antitrust lawsuit against Standard Oil under the Sherman Antitrust Act. The lawsuit was unprecedented in its scope and scale, involving over a thousand exhibits, 444 witnesses, and 12,000 pages of testimony. The government accused Standard Oil of engaging in monopolistic practices, including predatory pricing, collusion with railroads, and the systematic elimination of competition.

The trial was a spectacle that captivated the nation. Standard Oil’s defense hinged on the argument that its practices, while aggressive, were not illegal under existing laws and that the company had brought efficiency and stability to the oil industry. However, the sheer weight of evidence presented by the government was overwhelming. In 1909, the court ruled in favor of the government, declaring that Standard Oil had indeed violated antitrust laws and ordering the company to be broken up.

In 1911, the Supreme Court upheld the lower court’s decision, mandating the dissolution of Standard Oil into 34 separate entities. This landmark ruling was a significant victory for the antitrust movement and set a precedent for future cases. For Rockefeller, it was a dramatic turning point. The empire he had spent decades building was being dismantled.

However, the breakup of Standard Oil had an unexpected outcome. Instead of diminishing Rockefeller’s wealth, it significantly increased it. The individual companies that emerged from the dissolution, such as Exxon, Mobil, and Chevron, thrived as independent entities. Rockefeller’s substantial stock holdings in these new companies soared in value, making him even wealthier.

While the legal battles and public backlash were undoubtedly challenging for Rockefeller, they also marked the beginning of his transition from industrialist to philanthropist. With his business empire fractured but his wealth intact, Rockefeller turned his focus to charitable endeavors, seeking to reshape his legacy and contribute to society in meaningful ways.

Despite the controversy and scandals that marred his career, Rockefeller’s impact on the American economy and the global oil industry was undeniable. His ability to navigate intense public scrutiny and legal challenges showcased his resilience and adaptability. As he stepped back from the business world, Rockefeller prepared to leave a different kind of mark on history—one defined by generosity and philanthropy.

Philanthropic Legacy

After decades of ruthless business practices and accumulating unimaginable wealth, John D. Rockefeller turned his attention to philanthropy. The breakup of Standard Oil in 1911, while a public relations blow, left Rockefeller with an even greater fortune due to the skyrocketing value of his shares in the newly formed companies. Now in his early 70s, Rockefeller was ready to dedicate the rest of his life to giving back.

Rockefeller’s philanthropic efforts were rooted in the principles of the Baptist faith that his mother had instilled in him. He believed that his wealth was a gift from God, meant to be used for the betterment of humanity. Throughout his life, even during his business career, Rockefeller had consistently donated a portion of his income to various charitable causes, often anonymously to avoid public scrutiny.

In 1913, Rockefeller took a significant step by establishing the Rockefeller Foundation, a charitable organization designed to promote the well-being of humanity worldwide. He appointed Frederick T. Gates, his trusted advisor, and his son, John D. Rockefeller Jr., to oversee the foundation's activities. The foundation’s mission was broad, allowing it to support a wide range of initiatives in health, education, and scientific research.

One of the foundation’s first major initiatives was in the field of medicine. At the time, diseases like hookworm, malaria, and yellow fever were rampant, particularly in the southern United States. The Rockefeller Foundation funded extensive research and public health campaigns to combat these diseases. One of its most notable successes was the eradication of hookworm in the United States, which significantly improved public health and quality of life in affected regions.

In addition to public health, the Rockefeller Foundation made substantial contributions to education. Recognizing the transformative power of education, Rockefeller invested in institutions that promoted higher learning and research. He funded the establishment of the University of Chicago in 1890, which quickly became one of the leading universities in the world. His donations also supported the growth of Spelman College, a historically black women’s college in Atlanta, helping to provide educational opportunities to African American women in the South.

Rockefeller’s philanthropic vision extended beyond the United States. He was a strong advocate for international collaboration in scientific research. The Rockefeller Foundation provided grants to support research institutions and scholars around the world, fostering global advancements in medicine, agriculture, and the social sciences. These efforts helped lay the groundwork for modern scientific inquiry and collaboration.

Apart from his foundation, Rockefeller’s personal charitable endeavors were extensive. He supported numerous churches, educational institutions, and relief organizations. His donations were often guided by the belief in “scientific philanthropy,” a concept that emphasized careful planning and management of charitable activities to achieve the greatest impact. This approach was revolutionary at the time and influenced future generations of philanthropists.

Rockefeller’s son, John D. Rockefeller Jr., played a crucial role in continuing and expanding his father’s philanthropic legacy. Junior inherited not only his father’s wealth but also his commitment to charity. He spearheaded projects like the restoration of Colonial Williamsburg and the creation of the Rockefeller Center in New York City. Junior’s dedication to conservation led to the donation of land for national parks, including the Grand Teton and Acadia National Parks, ensuring that natural treasures would be preserved for future generations.

The impact of the Rockefeller family’s philanthropy is immeasurable. Their contributions have touched countless lives and advanced human knowledge in profound ways. The Rockefeller Foundation continues to operate today, addressing contemporary global challenges such as climate change, public health crises, and social inequality.

Despite the significant positive impact of his philanthropy, Rockefeller’s legacy remains complex. His ruthless business tactics and the negative public perception of his methods contrast sharply with his charitable endeavors. As historians and biographers have noted, Rockefeller embodied a dual legacy: one of immense wealth built through aggressive capitalism and another of unprecedented generosity and humanitarianism.

In the end, Rockefeller’s philanthropic legacy serves as a reminder of the power of wealth to effect positive change. It also highlights the moral complexities that often accompany great financial success. While opinions on Rockefeller’s life and career may vary, there is no denying that his contributions to society have left an indelible mark on history. As he spent his final years focused on giving back, Rockefeller transformed from a symbol of corporate greed to a pioneering figure in modern philanthropy.

Legacy

John D. Rockefeller's legacy is a tapestry woven with threads of both immense achievement and profound controversy. As the world’s first billionaire, he transformed the oil industry, set new standards for business practices, and amassed a fortune that changed the course of American history. Yet, his methods and their ethical implications have sparked debate for over a century.

Rockefeller’s rise from humble beginnings to the pinnacle of wealth is an inspiring tale of determination, ingenuity, and hard work. Born into a poor family in Richford, New York, he overcame significant obstacles to become a titan of industry. His journey from a young boy who sold turkey eggs to support his family to the head of Standard Oil is a classic rags-to-riches story that underscores the possibilities within the American Dream.

However, the methods Rockefeller employed to build his empire were often ruthless. He leveraged his financial acumen and strategic vision to outmaneuver competitors, often using tactics that many deemed unethical. Secret railroad rebates, predatory pricing, and aggressive acquisitions helped Standard Oil achieve near-total dominance of the oil industry. These practices stifled competition, leading to accusations that Standard Oil was a monopoly that hurt the free market and harmed consumers.

The public backlash against Rockefeller and his company was intense. Journalists like Ida Tarbell exposed the darker side of his business dealings, painting a picture of a man who valued profit over fairness. Her work not only influenced public opinion but also galvanized political action, leading to the landmark antitrust lawsuit that resulted in the breakup of Standard Oil in 1911.

The dissolution of Standard Oil was a significant moment in American economic history. It demonstrated the power of the government to regulate big business and marked the beginning of more stringent antitrust enforcement. Despite this setback, the breakup of Standard Oil inadvertently increased Rockefeller’s wealth, as the value of the newly formed companies surged. This paradox highlighted the complexity of Rockefeller's influence on the economy: his monopolistic practices were curtailed, yet his financial legacy was cemented.

Rockefeller’s transition from industrialist to philanthropist added another layer to his complex legacy. His establishment of the Rockefeller Foundation and other charitable endeavors showcased his belief in using wealth for the public good. His contributions to medicine, education, and scientific research had a lasting impact, saving countless lives and advancing human knowledge. The eradication of diseases like hookworm, the establishment of prestigious universities, and the support of global scientific research are all testaments to his philanthropic vision.

Yet, the duality of Rockefeller’s legacy remains a point of contention. Was he a ruthless monopolist or a visionary philanthropist? The answer is both. His life exemplifies the potential for wealth to bring about significant social change while also highlighting the moral complexities of its accumulation. Rockefeller’s story serves as a case study in the power dynamics of capitalism, the role of government regulation, and the responsibilities of wealth.

Rockefeller’s influence extended beyond his lifetime, shaping the business practices and philanthropic efforts of future generations. His innovative approach to both business and charity set a precedent for other industrialists, including Andrew Carnegie and later, Bill Gates and Warren Buffett. The concept of “scientific philanthropy” that he championed—using strategic, well-planned giving to solve societal problems—continues to guide modern charitable foundations.

In the end, Rockefeller’s legacy is a mirror reflecting the multifaceted nature of human ambition and impact. His life story is a reminder that great achievements often come with significant ethical questions and that the true measure of a legacy lies in its long-term effects on society. As his son, John D. Rockefeller Jr., aptly noted, "There was only ever one John D. Rockefeller," capturing the singular nature of his father’s remarkable and complex life.

While opinions on Rockefeller will always be divided, his story remains a compelling narrative of American industry, wealth, and the potential for transformation. It challenges us to consider the balance between ambition and ethics, success and responsibility, and ultimately, the legacy we wish to leave behind.